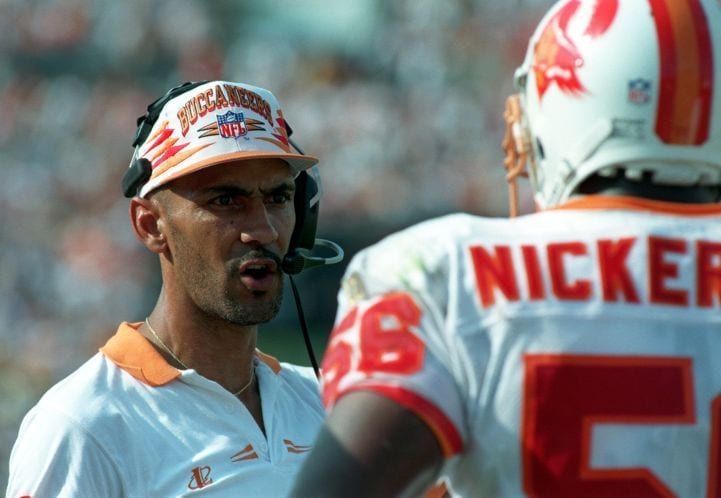

How do you define success? Chuck Noll said, “I would rather play well and lose than play poorly and win.” When I coached the Buccaneers, we had improved from 1996 to 1997, and we should have kept improving in 1998. Instead, we finished 8–8 with the most inconsistent playing of any team I’ve ever fielded. We’d play well one week and badly the next. Our problems weren’t only on one side of the ball. Our defense alternated between hot and cold performances. Our offense scored in bunches one week and then suffered through droughts. We had lost to Green Bay six times in a row then finally broke that streak by causing eight fumbles and sacking Brett Favre eight times. We handed 15–1 Minnesota their only regular-season loss. But we also lost to a 6–10 New Orleans team, twice to Detroit, and to Jacksonville when we blew a fourth-quarter lead.

We headed into the final game with a record of 7–8. If we won at Cincinnati, and if Arizona lost to San Diego, we’d be back in the playoffs—barely. We went on the road and finally put together a complete game, beating the Bengals 35–0. I was proud of our team. We were now relying on the San Diego Chargers, who had only five wins that season, to get us into the playoffs by beating Arizona. We watched the beginning of the game at the airport on the overhead televisions. Some of the guys clustered around tiny handheld televisions. We hung on every play. When our plane took off, San Diego was poised for a comeback win after being down 13–3 in the third quarter. Here’s the rest of the story.

A short time into our flight, the pilot’s voice came over the intercom. “Air traffic control knows whom I have onboard the aircraft this evening, and they wanted me to tell you congratulations on today’s game.” We all sat breathlessly. “They have also passed along the scores from the late afternoon games, including Arizona, who kicked a field goal on the last play to beat. . .” I didn’t hear the rest, even though our plane was silent.

Being a Steward of Opportunities

What distinguished the 1997 team from the 1998 team was not those two extra wins that put us into the playoffs. The 1997 team was simply a better steward of its opportunities. Every team has its own unique set of dispositions, gifts, talents, and opportunities. What they all have in common, however, is the ability to control what they do with those dispositions, gifts, and talents when the opportunities come along.

The 1997 team was younger with less depth and game experience. The 1998 team filled in some of those holes. On paper, the 1998 team was a better team. But our 1997 team stretched itself and achieved its potential. The 1998 team was inconsistent and squandered chances. I still believe what I told the team the day after the finale against Cincinnati: “We have a good team, but we didn’t take advantage of the opportunities we were given all year long. That’s why we had to rely on someone else. We cannot do that again.” The same is also true for each of us.

Doing Ordinary Things Well

That, to me, is where we find the best definition of success. We’re not all going to reach the Super Bowl or the top of the corporate ladder, but we each have a chance to walk away from something saying, “I did ordinary things as well as I could. I performed to the full limits of my ability. I achieved success.” Under that definition, a 5–11 team might actually be more successful than a 14–2 team.

I have no problem coaching a team that needs to win its final game and needs help from another team to get into the playoffs—as long as the team has played to the limits of its abilities and has fulfilled its potential. Our 1997 team played to and beyond its potential. Our 1998 team did not.

Sound off: What are some of the “ordinary things” we need to do well as dads?

Huddle up with your kids and ask, “Why do you think it’s important to always give your very best?”